In Part I, we covered Series LLCs and the core documents. In this article, we’ll turn to the regulatory frameworks.

In Part I, we covered Series LLCs and the core documents. In this article, we’ll turn to the regulatory frameworks.

For managers of private funds, there are three core laws they need to be aware of:

-

The Securities Act of 1933 (“Securities Act”) - which regulates the offering of fund interests to investors (determining which investors you can legally raise from and what steps you must take when offering such interests).

-

The Investment Company Act of 1940 (“Company Act”) - which regulates the investment vehicle itself (defining how many investors it can have, and what compliance limits apply).

-

The Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (“Advisers Act”) - which regulates the manager (sets the rules on when you must register as an investment adviser).

While the regulatory matrix of private funds can feel daunting, if you understand the basics and keep record for the legal documents we discussed in Part I, maintaining compliance can become a repeatable process.

Securities Act

When you bring an investor into your fund or SPV, the law treats that transaction as the sale of a “security” and fund managers must follow the rules that govern how securities are offered and sold. There are two ways to do this:

(1) registering the securities with the SEC (a costly, burdensome process); or

(2) relying on exemptions and safe harbors designed for private offerings.

Because registration isn’t practical for most fund managers, nearly all funds rely on exemptions, most commonly Regulation D, paired with notice filings at the state level. Together, these filings notify regulators that your raise qualifies as a compliant private offering (for a deeper dive, see our piece on VC Fund Regulatory compliance).

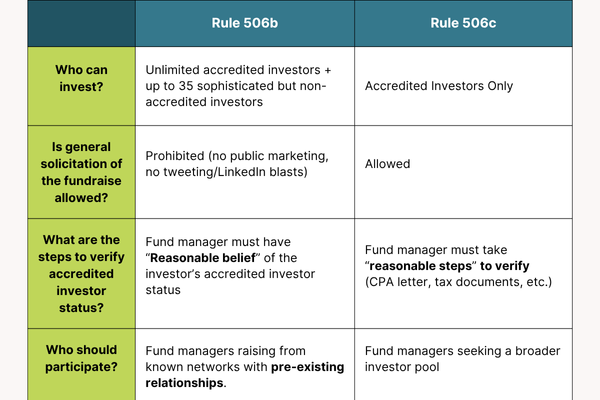

Within Regulation D, most fund managers rely on one of two exemptions: Rule 506(b) or Rule 506(c), explained briefly in the chart below:

For many, 506(b) is a natural fit when raising from a trusted network of investors. 506(c) works for fund managers who are soliciting investors (e.g., via social media or other advertising methods), but can also comply with the operational burdens of verification.

Whether you’re conducting a 506(b) or 506(c) offering, you have 15 days from the date of first sale to file Form D with the SEC and Blue Sky filings in each state where your investors reside.

Company Act

If the Securities Act sets the rules for selling securities to investors, the Company Act sets the rules for the fund itself, including how private funds are structured and how many investors they can include.

Like the Securities Act, the Company Act leaves fund managers with two options:

- Registering with SEC as an investment company; or

- Qualifying for an exemption.

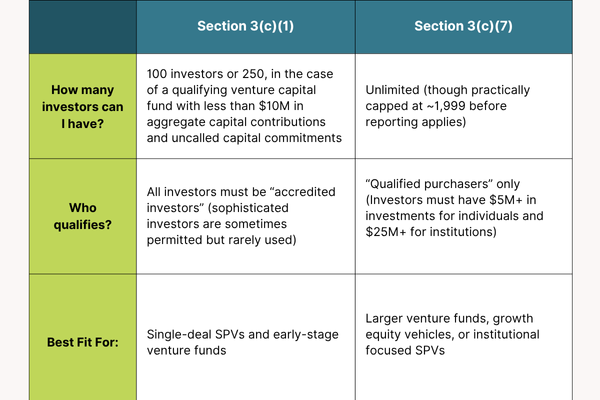

Many fund managers rely on one of two exemptions—Section 3(c)(1) or Section 3(c)(7). Both exemptions require that the fund is not making a public offering of its interests (506(c) offerings are not public offerings) and meets certain other requirements generally described in the chart below.

These exemptions are relatively straightforward to apply if you're able to navigate and understand the information collected in your Subscription Agreement and Confidential Investor Questionnaire.

Key Nuance

The limitation on the total number of beneficial owners of the fund’s securities is not as simple as looking at the number of subscription agreements you accept. For instance, for an entity investor, the fund needs to look through the number of beneficial owners of an entity when the entity is formed for the purpose of investing in the fund. Section 3(c)(1) also requires the fund to look through to any investor which itself would be an investment company (or would be an investment company (but for the Section 3(c)(1) or Section 3(c)(7) exclusion) and which has more than 10% of the voting securities of the fund.

To deal with this nuance, your Investor Questionnaire should include representations, warranties, and questions about each investor’s ownership structure and investment purpose to track and comply with these requirements.

Advisers Act

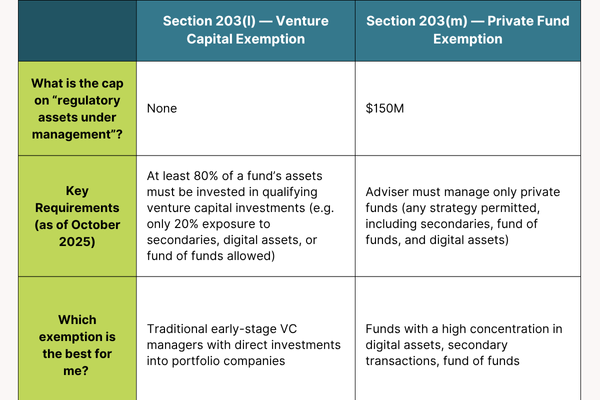

Finally, the Advisers Act governs you—the manager. Normally, anyone managing investments for compensation must register with either the state or the SEC as an investment adviser (depending on their regulatory assets under management). However, many advisers of private funds qualify for an exemption. The two most common are the Venture Capital Exemption (Section 203(l)) and the Private Fund Exemption (Section 203(m)), summarized below:

The Venture Capital Exemption

As the name implies, many fund managers deploying a venture capital strategy rely on the Venture Capital Exemption, which applies only if the manager solely manages vehicles that qualify as venture capital funds. If a manager oversees multiple SPVs or funds, every single one must meet the venture capital definition.

For example, if a manager operates ten SPVs and nine qualify, but one is structured as a fund of funds or focused on secondaries, the manager loses eligibility for the Venture Capital Exemption. In that case, they must rely on the Private Fund Exemption, which subjects them to the $150 million AUM cap.

Some managers try to sidestep this rule by forming a new management entity for non-qualifying vehicles. However, under the SEC’s integration doctrine, separate entities may still be treated as a single adviser if they share ownership, control, personnel, or operations.

How the DEAL Act Could Change The Venture Capital Exemption

Currently, the Venture Capital Exemption is narrow: funds can invest no more than 20% of their assets in non-venture holdings such as secondaries, fund-of-funds, or digital assets. This limitation is what often disqualifies hybrid SPVs or secondaries-focused vehicles from the exemption and triggers the RAUM cap discussed above.

The DEAL Act of 2025 (H.R. 4429) would broaden the definition of “qualifying investments” to allow up to 49% in secondaries and fund-of-funds while still meeting the venture capital standard. If enacted, it would give managers far greater flexibility to diversify across fund types—making it much easier to maintain compliance even with mixed portfolios.

Summary

By leveraging standardized documents from Part I, such as Subscription Agreements to verify investor eligibility and track exemptions, managers can turn compliance into a streamlined, repeatable process that minimizes third-party dependence.

Stay tuned for Part III, where we'll tackle tax and operational essentials to round out your in-house setup.

This post comes from Shayn Fernandez and Justin Bell at Junto Law, legal advisors to emerging fund managers as they raise funds, make investments, and navigate complex regulations.

Disclaimer: While this article was written by lawyers who enjoy operating outside the traditional lawyer and law firm “box,” we are not your lawyers. Nothing in this post should be construed as legal advice, nor does it create an attorney-client relationship. The material published above is only intended for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes. Please seek the advice of counsel, and do not apply any of the generalized material above to your facts or circumstances without speaking to an attorney.